On December 6, 1889 Thomas Stacey took over the Railway Hotel at Bunyip from Sarah Hansen, even though she still retained ownership of the property. It was a unhappy relationship as in the next five years they were involved in multiple legal cases with each other.

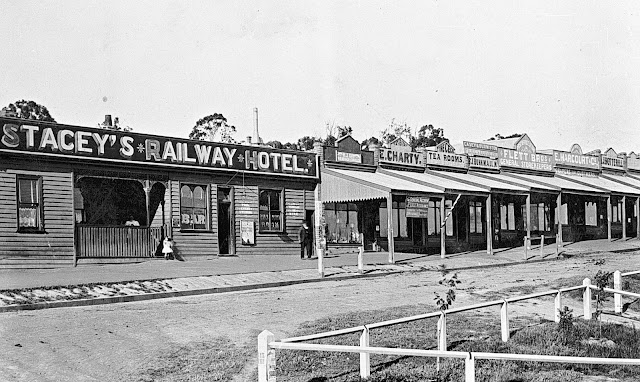

The Railway Hotel, Bunyip, c. 1905 - the source of the contention

between Mrs Hansen and Mr Stacey.

The Railway Hotel was started in the late 1870s by William Hobson who married Sarah (nee McKernon) in March 1879. After William died, Sarah continued to operate the Hotel on her own. She married Christian Hansen in 1885. She sold the business (but not the property) to Thomas Stacey in 1889. He operated the Hotel until his death in January 1928 at the age of 77. Sarah died in October 1913, aged 73. Sarah had four children to William Dethmore before she married William Hobson. Her daughter Christina Dethmore is involved in two of the cases. I have more details on the hotel and the family here.

Here are some newspaper reports about these legal cases between Sarah Hansen and Thomas Stacey.

From the Warragul Guardian, August 12, 1892 (see

here)

Warragul County Court,

Wednesday, 10th August, 1892

(Before His Honor Judge Worthington)

Libel Action -Damages £3.

Thomas Stacey, hotelkeeper, Bunyip v. Sarah Hansen, claim for £49 for alleged libel contained in a letter addressed by defendant to Sergeant. Hillard, of Warragul. Mr. James Gray appeared for the complainant, and Mr. D. Wilkie defended. The alleged libel was contained in a letter from the defendant to Sergeant Hillard as follows:-

" Dear Sir--I must call your attention to Stacey's hotel, at Bunyip, last Tuesday week. There were two drunken men in and out the place during Tuesday. The night before last and last night we could not sleep for noise there all night. I hear there is going to be a dance there to-night. There seems to be an open house there day and night. I have got the Church of England minister staying with me, and I think it is time their conduct was seen into, as there are drunken women and men singing all night. I think it would be wise to send some one in plain clothes. By doing so you will oblige, as it is my property, and I must have it seen to."

Mr. Gray submitted that the language was too strong to be privileged. The relations between the parties had been strained for some time. The defendant lived 200 yards from the plaintiff's hotel, and the allegations in the letter were perfectly foundationless.

Mr. Wilkie pointed out that he had received two summonses (Nos. 93 and 94), and as the former had not been filed, he was at a loss to know on which the complainant was proceeding. He contended the letter was a privileged communication, that it was written without malice, and in the public interest. The point raised by Mr. Wilkie respecting the two summonses was argued at length, and was finally overruled, his honor merely asking down the grounds of Mr. Wilkie's objection - two summonses had been served in the case, No. 93 was served some days previous to No. 94. That at the time No. 94 was served no notice of discontinuance had been given in the action, and that therefore the second summons (No. 94) was invalid, and on that ground he applied to have the summons set aside and struck out.

Robert Hillard, sergeant of police, stationed at Warragul, was then called. Mr. Gray,: Do you produce any document? Mr. Wilkie: I thought that any communication sent to witness was privileged. His Honor allowed the question with the understanding that the witness could consider it privileged if he chose. Witness (continuing): Had had notice to produce a letter. Did not feel he could very well object to produce the letter (letter put in.) On receipt of the letter he sent it to Constable Trainor, of Longwarry. Mrs. Hansen had called at his (witness') office. She said that her daughter had written the letter for her, and that she had not written it, or words to that effect.

Constable Trainor enquired into the complaints contained in the letter. To Mr. Wilkie: It was not the practice for the police to disclose the name of an informer. It would be an improper thing for a constable to show the letter to anyone. It was confidential. Constable Trainor went on the evening of the 3rd July. Anthony Joseph Trainor, stationed at Longwarry, said that on receipt of the letter from Sergeant Hillard he went to Bunyip to make enquiries.

Mr. Wilkie submitted that the witness should not state the result of his enquiries. Mr. Gray: If there was no foundation for the expressions in the letter, and they were proved to be groundless then the expressions were libellous. Mr. Gray (to witness): What was the result of your enquiries? Mr. Wilkie: I object. His Honor upheld the objection.

Witness (continuing) said: I saw Mrs. Hansen on the 3rd of July. Went the same evening that he received the letter. Mr. Wilkie again objected, contending that the conversation between the defendant and witness had no right to be disclosed, otherwise people would be afraid to complain to the police. His Honor held that the evidence was permissible. Witness said that when he called upon the defendant she said that the contents of the letter were quite true. There had been two drunken men in knocking about on the Sunday in and out of the hotel, and that she saw Stacey pushing them about. He witness) asked who they were. She replied, "Two men in the employ of Stacey. Their conduct was very bad, singing at all hours of the night. There were drunken women too. She heard them singing going home at night in a dray, and thought one of the women was a boarder at the hotel, or she only heard so. The minister complained about the noise during the night; it was time it was put a stop to"

He (witness) said- "why did you not tell me ?" She replied that a stranger would be best, I was too well known. Defendant's husband came in and said he had not noticed any misconduct at the hotel, and asked who had been reporting it? Witness replied "Mrs. Hanson has been reporting it. He replied, "She has no right to complain or write letters, it had nothing to do with her." The defendant had made previous complaints. He (witness) said, " It is strange you are always making complaints about the hotel. I cannot find anyone else in the township that sees anything wrong. You must have some motive in saying so." Defendant replied, " Yes, I have a motive. The place is not half insured; it is my property. They promised to insure for £400 when they took it from me, and have not done so. If is only insured for £200, and they might burn it down any time."

To Mr. Wilkie: Knew the rule in the police force, and that they should not reveal an informants name. He did not reveal the name, and did not show the letter to anyone. Could not say how Mr. Gray got the letter. Never saw it after sending it back to Sergeant Hillard. Told Stacey there was a complaint about his hotel, and who had complained, and what the complaints were. He had no reason to complain about the hotel. Heard Stacey had been fined for Sunday trading. Was not annoyed about the letter himself. Never told Stacey that the words were actionable. Mrs. Hansen did not say she did not want to make a charge.

Thomas Stacey, the plaintiff, was licensee of a hotel at Bunyip. Had purchased the place from Mrs. Hansen two years ago, and been in the premises ever since. Heard about the letter. There was not one truth in the statements made by Mrs. Hansen. Had been on bad terms from two months after he took possession of the house. On one occasion had put a man out of the hotel. She said that he (witness) had insulted her and summoned him at the Drouin Court, when the case was dismissed with costs.

To Mr. Wilkie: Did not now where Mr. Gray got the letter from. He had bought the hotel. Did not pay any money down. Mrs. Hansen lent him money. Had executed a mortgage to Mrs Hansen and was a tenant of hers in the meantime. Had agreed to rebuild the premises at an outlay of £450. Did not as a rule serve people on a Sunday. Admitted that a woman was dressed in men's clothes at the hotel and singing. To Mr. Gray: From what Constable Trainor had told him he came to see Mr. Gray. There were no drunken women on the place.

David Evans, storekeeper in Bunyip, said he did not hear any noise about the date mentioned. Knew that Mrs. Hansen disapproved of the way the house was conducted, but could not remember what she had said. Harold Nixon, Church of England minister as Bunyip. Remembered living at Mrs. Hansen's at the beginning of July. Never complained to Mrs. Hansen about Stacey's hotel. Did not remember any noise. It was not true that he complained about a noise to Mrs. Hansen. To Mr. Wilkie: Had said on coming down to breakfast one morning " what was that noise in the street last night."

George Farrow, selector, lived five or six chains from the hotel. Never complained about the hotel. Did not take any notice what Mrs. Hansen had said to him. Did not expect to be brought up as a witness. No one spoke to him about this case. Had heard Mrs. Hansen say that Stacey would be out of the place in three months, and that she could not see what kept him there, but she did not say that she would hunt him out. He had said that Mrs. Hansen was worth leaving alone. He did not want to be mixed up in a neighbor's quarrel. Never spoke to Mrs. Hansen about this case.

This concluded the base for the plaintiff. Mr. Wilkie submitted that there was no case. No proof had been adduced that Mrs. Hansen had written the letter containing the alleged libel. He contended that the letter did not contain any allegation of a breach of the Licensing Act, it was a general complaint, and it was hard to see how plaintiffs business or credit could be affected. His own evidence had shown that names of informants should not be disclosed to the public; and it was well known that defendant had an interest in the property and had a right to complain. There was no evidence of malice, or of a vindictive motive, and on the other hand plaintiff had been allowed absurdly easy terms to pay for the property. And a complaint made to an officer of police of alleged misconduct should be treated as privileged. Sergeant Hillard had said that the letter should not have been shown to any one.

At this stage the court adjourned for lunch, on resuming - His Honor: said that there was not a case for a jury, but he held that some of the evidence went to show that defendant desired to get complainant out of the hotel. He would therefore hear the defence.

Mr. Wilkie was at some loss what to answer. According to his view there was actually no evidence of a libel.His Honor thought there was, and he therefore asked for the defence. Mr. Wilkie contended that it His Honor held that malice had been proved, his evidence could not alter that belief.

Christina Detmore, daughter of the defendant, said she wrote the letter. The letter was written on July 1st. The night before she heard noises at the hotel, principally singing. Knew that it came from Stacey's hotel. The Rev. Mr.Nixon said on that morning that he had heard noises in the night. Her mother told her to send a note to Mr. Hilliard about the noise the night before: Wrote the letter about 9.30 on Saturday morning. Her mother did not tell her what to write, nor did she see what was, written or was aware of the contents, as the letter was written hurriedly. Previous to this time she had seen drunken men about the place, and had heard singing at night.

To Mr. Gray:- Wrote a good many of her mother's letters but not all. Was quite positive that she did not tell her mother what was in the letter until afterwards. Hardly remembered the contents of the letter until she saw it in the summons. There were no houses between their's and Stacey's. Never told anyone that they had a few pounds as well as Stacey and would fight him. She wrote the letter without her mother knowing anything about it. To Mr. Wilkie: She told her mother about a portion of the letter.

Sarah Hansen, the defendant, said she remembered the 1st July. Heard a noise that night after 12. It came from Stacey's. Her daughter's evidence was correct. She told her daughter to write to Sergeant Hillard, as she could not rest at night. She did not know what had been written until she got the summons. Had sold the place to Stacey, but could get no satisfaction. She was always insulted. When asked to insure the place he treated her in a most vulgar manner. Had told Constable Trainor that the place was not insured and therefore was in danger. To Mr. Gray: This was not the first libel action she had been concerned in. Her daughter only told her a portion of the letter. Was sent to trial for perjury on one occasion. To Mr Wilkie: The charge of perjury was dismissed.

In closing the case for the defence Mr.Wilkie remarked that he must repeat what he had previously stated - that there was no case - and held that the mother could not be held responsible for what her daughter had written. His Honor had admitted that the communication was a privileged one, therefore the plaintiff must prove a strong case in order to secure a verdict. It had not been shown how the letter had been made public. Sergeant Hillard had stated that it should have been confidential, and Constable Trainor denied showing it to anyone. Mr. Gray contended that if Mrs. Hansen said she did not know what was written in the letter she told a lie, as she must have been aware of the contents. The letter was full of innuendos of a libelous nature. The statements had been made broadcast, and there was no attempt to deny them.

His Honor held that the letter was defamatory, but that it was privileged being addressed to the police. The complainant was a debtor and did not keep his covenants; but the defendant had not gone the right way about. He gave a verdict for £3, costs to be taxed.

Warragul Court House, where Sarah Hansen and Thomas Stacey

conducted some of their legal battles.

Warragul Court House, Smith St. Photographer: John T. Collins. Photo taken March 8, 1971.

State Library of Victoria Image H98.251/2439

, see

here.

Slandering a young woman.

Claim for £250 Damages

She recovers £60.

Action at Warragul.

At the adjourned sitting of the Warragul County Court on Friday, before His Honor Judge Hamilton, a young unmarried woman of ladylike appearance, about 22 years of age, named Christina Dethmore, brought an action to recover, a sum ot £250 from Thomas and Ann Stacey, hotelkeepers at Bunyip, for alleged slander, based on the circulation of the report that the plaintiff had had two children. Mr. Johnston (instructed by Mr. Wilkie) appeared for plaintiff, and Mr. Lyons (of the firm of Lyons and

Turner) defended.

Mr. Johnston, in opening the case said the action was being brought for slander uttered by one of the defendants - Mrs. Stacey, wife of Thomas Stacey, hotelkeeper, Bunyip. The plaintiff, Miss Dethmore, was the daughter of Mrs. Hansen, her step-father being Mr. Hansen, Mrs. Hansen's second husband. The Hansens were also hotelkeepers up to three years ago, when they sold their hotel at the Bunyip to the Staceys - the defendants in the case. Ill-feeling arose subsequently between the Hansens and the Staceys, and Mrs. Stacey had chosen to vent her spite on the daughter - Miss Dethmore - by circulating the baseless slanders which were the subject matter in the case. He did not know what the defence would be - no defence of justification, at any rate, had been filed, and he would therefore ask His Honor to call on defendant's counsel for the defence. Mr. Lyons said the defence was one of not guilty - that the defendants did not utter the slander, and that there was no publication.

Esther Johnson, unmarried woman, engaged in the service of Mr. and Mrs. Stacey in August last, was then called and said: She left their employ after being there a month. The same day as she entered their service Mrs. Stacey said that the plaintiff was the mother of two children. She also said the Hansens were bad people and advised witness not to have anything to do with them. At this time witness knew nothing of the plaintiff or the Hansen family she subsequently repeated the allegations on several occasions. On one of these occasions Mrs. Stacey and witness were standing on the verandah of the hotel when the plaintiff passed and Mrs. Stacey remarked, "You would never think to look at her that she was the mother of three kids" Witness left Mrs. Stacey's employ shortly afterwards.

Cross-examined by Mr. Lyons: Mrs. Stacey had always treated witness well. She had never previously ever heard anything of the Hansens or the plaintiff. Witness did not tell Mr. Stacey at Longwarry station, that she was dragged into the case and wished she was out of it.

Annie Roberts, married woman, said her husband carried on a bakery business at Bloomfield. She knew Mrs. Stacey and was on one occasion standing on the verandah of the Hotel with her when Miss Dethmore passed. Witness remarked to Mrs. Stacey that Miss Dethmore was rather proud and Mrs. Stacey replied that she had nothing to be proud of and that she had had a child which her mother was keeping. Cross-examined: Witness was still on friendly terms with Mrs. Stacey.

Amy Roberts, daughter of the last witness, said she was in Mrs. Stacey's employ within the past 12 months. Mrs. Stacey told witness that Miss Dethmore had had two children and that her mother was keeping them in Melbourne. Annie Cain, married woman, not at present living with her husband, said she was at Mrs. Stacey's hotel on the 10th of June last and stayed there one night. Mrs Stacey asked witness if she knew Mrs. Hansen and witness answered "No" Mrs. Stacey then said that Mrs. Hansen's daughter was the mother of two children and that one of them was in Melbourne and that when Mrs. Hansen went to Melbourne she frequently went to see the child.

Plaintiff was then called and said she was engaged to be married. She first heard of the slanders on or about the 6th of August. Cross-examined by Mr. Lyons: The first witness heard of the slanders was from Mrs. Cain who said "I have heard about all the kids you have had and what you did with them." This was the case for the plaintiff.

Mr. Lyons then opened the defence briefly and called the defendant, Mrs. Stacey, who said that she advised Esther Johnson not to have anything to do with the Hansen family as they were not on friendly terms. She did not say that plaintiff was the mother of two children but that she had heard that she had had a child. Witness did not remember mentioning anything in the matter to Amy Roberts, and did not have the conversation alleged with Mrs. Cain.

Cross-examined by Mr. Johnston. Witness's husband in July brought an action for slander against Mrs. Hansen and won the case. Mr Johnston: Who was your solicitor in the action? Defendant: Mr. Gray. Mr. Johnston: Just so - that is quite enough to account for you winning the case.

Mr. Lyons then addressed his Honor and agreed that whatever might have been said by Mrs. Stacey to the witnesses who were at that time in her employ, was privileged, and was said as a warning out of regard of their moral welfare. The same might be said in regard to Mrs Roberts, who was spoken to by Mrs. Stacey, as she was the mother of the girl in her employ and was entitled to know it. The whole affair was only tittle tattle among neighbours and consequently was not a case in which heavy damages should be given. There was no evidence whatever against the husband, he had done nothing whatever to circulate the report, and therefore it would be hard, make him liable in any serious degree. The plaintiff had not been in any way ignored in the eyes of her friends or neighbors and having regard to all the circumstances of the case very small damages would suffice to rehabilitate the character of the plaintiff.

Mr. Johnston said he could not find any mitigating circumstance in the conduct of the defence. He ridiculed Mrs. Stacey's professed concern for the moral welfare of the servants in her employ and asked for substantial damages.

His Honor said that in his opinion the slander was a false and foul calumny on the reputation of the plaintiff and that she was entitled to such damages as would show that the court considered she had been grossly wronged. He, however, was not disposed to give exorbitant damages because it might mean ruin to the husband who, although legally responsible for his wife's torts, had done nothing to spread the reports. A verdict would therefore he given for the plaintiff with £60 damages and costs.

Gooddy's of Grattan Street. A bill from Gooddy's was the cause of a legal case between Sarah Hansen and George Stacey (see below)

From the Narracan Shire Advocate, May 6 1893, see

here.

Peculiar Perjury Case

A considerable amount of public interest was manifested in a case heard at the Warragul Police Court before Messrs. D. Connor and P. J. Smith, Js.P., on Tuesday, when Sarah Hansen preferred a charge of wilful and corrupt perjury against George Stacey. The proceedings arose out of an action heard at the Warragul County Court in November last, when Mrs. Hansen sought to recover a sum of money from Stacey for certain empty bottles and cases which he was alleged to have neglected to return to L. Gooddy and Co., aerated water manufacturers, Melbourne according to agreement, and with which she was consequently charged, as the order for the stuff was sent through her as the owner of the Railway Hotel Bunyip, of which Stacey was the licensee. The evidence on that occasion was very conflicting, and the judge dismissed the case.

Mrs. Hansen subsequently determined to proceed against Stacey for perjury and on the 20th of April last swore an information in which she alleged that Stacey committed wilful and corrupt perjury by stating that "he never received from the said Sarah Hansen any cases, lemonade, or ginger ale, except 5 or 6 dozen mixed cordials, lemonade and squash." Mr. Gray, at very short notice, appeared for Mrs. Hansen, and Mr. S. Lyons (Melbourne) defended.

Mr. Gray gave a lucid explanation of the informants case, as set forth in the following evidence, and then called Mrs. Hansen, who said: I am the wife of Christian Hansen, residing at Bunyip. I recollect the 6th December, 1889, on which date Stacey purchased my business and took over my house - the Railway Hotel, Bunyip. He took over the portion that was left of the stock. Some time prior to this -about a fortnight or three weeks - he asked me to get him a supply of lemonade and ginger ale and other cordials. I promised to do so, and did so. The order was complied with and tbe things were delivered at the house two days after he took possession. About 8 or 9 months after this - when he paid me for the things - I asked him if he had sent back the empty bottles and cases to the firm I got them from, and he said "Yes"

An account of all the goods he received was drawn up and sent to Stacey. I asked him for the receipt of all the empties that had been returned to Gooddy. He said "I have the receipt in the house and will give it to you when I find it" I had at this time paid the account for the lemonade and other drinks to Gooddy and Co - the amount being £3 2s. This was the stuff which was delivered to Stacey, and it was in reference to this account that Stacey said he had returned the empty bottles and cases in which the

stuff was sent. The items contained in the book (produced) were read over to Stacey and were agreed to by him except one or two items. He wanted to take out the item for £3 2s. from among the other items and asked for a separate account for it. I said "I will not have my books interfered with and refused."

He then paid me the whole of his account, including the £3 2s. About 12 months after I told Stacey he had deceived me as he had not returned the empty bottles and cases to Gooddy and Co. I told him I had received a notice from the firm in the matter and he told me I could go and do the best I could. I was compelled to pay for the empties myself, prior to which I had received a County Court summons from Gooddy and Co., and on telling Stacey this he said, "Hook it and do the best you can" I then paid the amount claimed by Gooddy, and costs. Subsequent to this I made a demand for the amount from Stacey, and he refused to pay.

I then sued him in the Warragul County Court. I gave evidence when the case was heard at the County Court, and Stacey gave evidence too. He said that he had never had the empty bottles and cases referred to. He said he had had nothing but 5 or 6 dozen of mixed cordials and squash, and that he had never received the bottles and cases she sued him for.

After some corroborative evidence had been given, Mr. Lyons called the defendant, who said: I am a publican at Bunyip, and was defendant in the case, Hansen v. Stacey, on the 17th of November. I remember Mrs. Hansen's bill being shown to me. I never swore I had never received any goods from Gooddy through Mrs. Hansen. I did not say I had never received 22 dozen of aerated waters from Mrs. Hansen. I said I had got some stuff through Mrs. Hansen from Gooddy, but that I could not remember the quantity. I then produced the bill, and showed where I had paid for the stuff. The contents of the bill of the staff received by me from Gooddy was not read over to me. I cannot read. When I said I only received 4 or 5 dozen of stuff I referred to the aerated water I had taken over from Mrs. Hansen when taking possession. Gooddy's stuff came in afterwards. When I paid the account to Mrs. Hansen I understood I had paid Gooddy's bill, as that was one of the items in Mrs. Hansen's account.

Cross-examined by Mr. Gray: When settling up with Mrs. Hansen the items were read over to me by Mrs. Shields. After I took possession of the hotel I received some stuff from Gooddy, but could not say the quantity. It was a good lot, and I thought I had paid for it in the bill I settled with Mrs. Hansen. I don't remember Mrs. Hansen coming to me in reference to the demand for the return of the empties. I returned the empties to Gooddy. I never told Mrs. Hansen that I would produce a receipt for the empties. I did not send the empties back myself. I told my man to do so, but I don't remember whether he did so.

At this stage the Bench intimated that they intended to dismiss the case. The charge was a very serious one, and they did not consider that there was sufficient corroboration to justify them in arriving at the conclusion that a prima facie case had been made out.

The Supreme Court in Melbourne, where Thomas Stacey took action

against Sarah Hansen in December 1894.

Law courts, Melbourne, c. 1888-1890. Stata Library of Victoria Image H7942

From The Argus, December 11 1894, see

hereAction under a Mortgage.

Exercise of power of sale

In the Supreme Court yesterday, Mr. Justice A'Beckett decided on action brought by Thomas Stacey against Sarah Hansen, to restrain the defendant from exercising the power of sale contained in a mortgage deed. Mr Mitchell, instructed by Messrs Lyons and Turner, appeared for the plaintiff, and Mr Bryant, instructed by Mr J. E. Dixon, for the defendant.

The plaintiff by his statement of claim stated that in October, 1889, he possessed certain property in the parish of Bunyip, county of Mornington, and in Collingwood, and mortgaged it to the defendant to secure the repayment of £725 and interest. He covenanted in the mortgage deed to insure against fire in the name of the mortgagee, but no amount was specified. There was no express covenant for repairs. It was provided that the plaintiff should be entitled to continue the security for a further term of five years upon giving certain notices. The plaintiff did insure against fire in the name of the mortgagee, and kept the buildings and improvements in repair, and made no default in payment of principal or interest.

In February, 1894, he gave notice to the defendant of his desire to continue the security for the further term of five years, but the defendant refused to do so, on the ground that there had been breaches of covenants to insure and repair, and she notified that unless the principal and interest were paid within a month she would at once proceed to exercise her power of sale. The plaintiff asked for an injunction to restrain the sale, and a declaration that he had not disentitled himself to the extension of the mortgage. The defence was that by a memorandum of agreement contemporaneous with the mortgage the plaintiff agreed to rebuild a certain hotel which had been burnt down, and to insure the new building for £450, and also the buildings on the other land for their full insurable value. The plaintiff, it was alleged, failed to effect the insurance for £450, or to keep the buildings in proper repair, and was disentitled from obtaining a renewal of the mortgage.

Mr Justice A'Beckett held that there had been no breach of the covenant to repair, but that there had been a breach of the covenant to insure to the full insurable value. The agreement to insure the hotel for £450, however could not be construed as a covenant under the mortgage, and the plaintiff was never properly called upon to perform the covenant to insure contained in the mortgage. Then the defendant had failed in the notice which she gave of her intention to exercise the power of sale, to state which covenant was said to have been broken, and the question arose whether this was rendered the notice bad. His Honour considered that it did.

Where the covenants were numerous it was quite possible for the mortgagor unconsciously to overlook one of them, and it seemed a reasonable interpretation to put upon the act that where a mortgagee was about to take such an extreme measure as to sell for the non-observance of a covenant, and where the mortgagor might avoid the consequences of that breach by remedying it within a month, the mortgagee was bound to state precisely the covenant which he alleged to have been broken. Judgment would therefore be entered for the plaintiff, with costs.

No comments:

Post a Comment