Up until 1976 a jilted party could sue their former fiancee or fiance for a 'breach of promise' for not going ahead with the marriage and ask for compensation or damages. In November 1911, a Breach of Promise case was reported in many newspapers and it concerned 24-year-old Charlotte 'Lottie' Flavelle Ewen, formerly of Garfield and 33-year-old William Park Temby of Iona, however his address is listed as Bunyip in the newspapers reports. Charlotte claimed £1000 in damages.

Before we look at the case we will have a look at the people involved and their life before and after the Court case.

Charlotte Flavelle EwenThe Paynters then purchased four blocks of land in the Iona Riding of the Shire of Berwick near Garfield, which they held until around 1914, when the Electoral Rolls indicate they had moved to Melbourne. (2)

Charlotte and Herbert had a daughter, Marjorie Jean in 1909; and then sadly on June 24, 1910 Herbert died at the age of 29, which left Charlotte a widow with a little baby. (3) She then moved in with her parents at Garfield and her life there is laid out in the reports of the court case, which we shall come to soon.

In 1914, Charlotte married John Nichol Baird and they initially lived in Newmarket, before moving to New South Wales, where she died at the young age of 31 on November 11, 1918. (4)

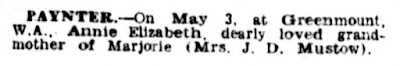

As for little Marjorie, it appears that she may have been raised by her grandparents, as suggested by the following death notices of her Grand-parents, Alfred and Annie Paynter -

William Park Temby

William was born in New South Wales in 1878 to James Mitchell and Jane (nee Park, also called Jean) Temby. After they moved to Creswick in Victoria, two more children were born - Mary Louisa in 1881 and a brother, James Mitchell, in 1882 who died aged 5 months on April 6, 1883. (5) Little James' death was the second blow the family faced in a few months, as on December 11, 1882 James was one of 22 miners who were killed in Creswick when the Australasia Mining Company mine was flooded. This left Jane with two small children, and even though all the widows and orphans received weekly payments from a relief fund which was established it would never make up for their loss (6)

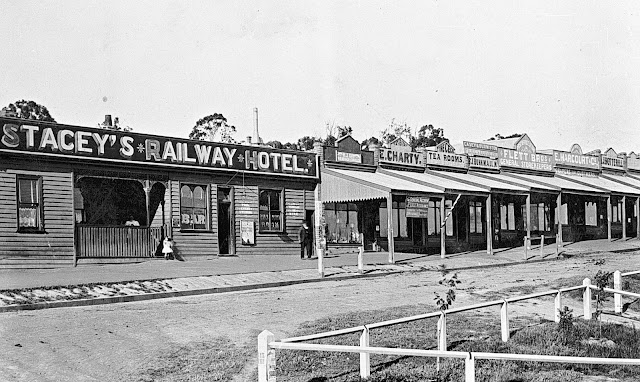

Jane, William and Mary Temby took up land in the late 1890s on the Koo Wee Rup Swamp (hence the reason William is called a village settler in the court case reports) on Fallon Road with some on the corner of Temby Road, which was named after the family. (7) When the Temby's arrived the area was known as Bunyip South and the name changed to Iona in August 1905.

After William and Charlotte split up, William married Beatrice Ewen on February 18, 1914. Beatrice (nee Beattie) was the widow of Arthur James Ewen; Arthur was the brother of Charlotte's first husband, Herbert John Ewen. Herbert and Beatrice had married in 1902 and he died the next year on September 10, at the age of 25, a tragedy for the family. (8) It's an interesting match, Beatrice was living with her parents-in-law, George and Catherine Ewen, at 120 Park Street, Brunswick at the time of her marriage to William Temby. Did they know each other before the breach of promise case or did the Ewens reach out to William after the case?

William and Beatrice lived on the family farm and Beatrice died September 8, 1950, aged 75, whilst William died on August 18, 1957 aged 78. The last few years of his life he was living in Surrey Hills. (9) Did they have children? The plaque on Jane Temby's grave at Bunyip also lists - Baby Grace Battie Temby passed away 11 March, 1919, which is their daughter, but I can't find a reference to either her birth. (10)

The Breach of Promise case

The case brought by Charlotte Ewen against William Temby was held in the County Court in Melbourne in November 1911.

From The Age of November 18, 1911 (see here)

BREACH OF PROMISE CASE. YOUNG WIDOW AND FARMER. £1000 CLAIMED.

Mr. Duffy, K.C., and Mr. Stanley Lewis (instructed by Messrs. Backhouse, Skinner and Hamilton) appeared for plaintiff; and Mr. Meagher (instructed by Mr. Davine, of Warragul) for defendant.

The formal defences were a denial of any breach of promise; that the engagement was broken by plaintiff; and, further, that it had been agreed between the parties that the marriage should be postponed for three months.

Plaintiff gave evidence that after the death of her husband she went to live with her father and mother at Garfield, in the Gippsland district, her father being a farmer there. She became acquainted with defendant, and they were engaged to be married. That was about a week before Easter of the present year. On Sunday, 30th July, she went with her father to see defendant, who was slightly ill. He lived with his mother and sister about six miles away. After afternoon tea his mother and sister left the room, saying it was time to milk the cow. Her father went on the verandah for a smoke.

This was a love match? - Yes. I have been a widow for twelve months, and have a child. Before I was married to my late husband I was engaged to a Mr. Chick. I broke that engagement off. I was 18 years of age then, and am 24 now.

Why did you break off your engagement with him? - Well, he asked me such a lot of questions about the furniture I had that it was apparent that he was not marrying me for love, and so I gave him up.

Did your husband leave you about £100? - No, about £300. There were no debts to pay. I know a young man named Arthur Dorey. I took him out twice for a drive whilst he was staying at my father's place. I have known him since I was a child. I was never engaged to him. Does that list include all your lovers? - Yes. I was very fond of Temby; but his conduct cured me. I cannot say I hate him.

Did you ever tell anybody that you thought Temby had a lot of money, but that it turned out to be his mother's? - No.

Did you not say that you had had a narrow escape? - Certainly not. There was no suggestion by defendant that the marriage should be postponed. I should have been glad to have waited, as I did not want to be married so soon after the death of my husband. I was utterly surprised when he broke the affair off.

He didn't embrace you or kiss you at that interview? - No, he did not; we used not to spend our whole time in doing that kind of thing. (A laugh.)

You wrote him an indignant letter? - I was very much upset when I wrote that letter. My indignation had been growing all the week. You said in the letter, "Knowing what I do now of you and your mother, I thank God for what I am saved from." So you are glad you did not marry him? - Yes.

You complain of "mean, low, cunning, despicable cold cruelty" - a fine, set of adjectives? - Yes.

Again - "You are a low down lot," "mother's crying Willie." That was defendant? - It was.

"How you have deceived me and my parents" - Was that about him not having £4000? - Yes. I do not say he is a good mark for damages. I was willing to accept £500 to compromise the case. All I want is to have my character cleared. When a man gives up a woman in the way he did me, some people might infer a lot. What about when you gave the other poor fellows up? - Oh, that don't matter.

(A laugh.) I want to punish him for the way he treated me. What's sauce for the gander is sauce for the goose? - Not always. That's women's rights with a vengeance. Ought you not to be punished for giving up the other men? - No, certainly not.

You wrote that you "would be glad to get away from such a miserable crew"? - Yes; that's the man's mother, his sister and himself. I have felt thankful since that I got away from them. I think I had a narrow escape. You had a ring and a watch which were given to you? - Yes, I have them now. I did not send them back again. I think I was entitled, to keep them in the circumstances.

Alfred Paynter, father of plaintiff, stated that he visited defendant's place. The latter said there were 125 acres, worth £30 an acre. There were 75 head of cattle, and he had a good banking account. The land and cattle, he said, were all his.

Mr. Meagher, in opening the case for defendant, alluded to plaintiff as "an attractive, but business-like and dangerous young widow." In "The Pickwick Papers" the elder Weller told his son Samuel to "beware of widows." That advice remained good to the present day. No doubt defendant fell in love with this widow and proposed marriage. In the circumstances no one could blame him. Being attacked with influenza, however, he wanted the marriage postponed. Plaintiff demurred to the proposal. This was first made on the Saturday. On the Sunday the father came to defendant's house with his daughter. The marriage was ultimately only broken off by the extraordinary and abusive letter plaintiff wrote to him.

Plaintiff thought defendant was worth £4000. When she found that he had very little money and would not be much of a "catch," she was glad of an opportunity of breaking off this engagement, as she had done others.

Defendant gave evidence that he was 33 years of age, and was a village settler. He had 53 acres of leasehold land. The value was about £13 per acre. He had a little machinery and about £5 in the bank. He never told plaintiff's father that he possessed £4000. He became engaged to plaintiff. She was given a ring of the value of £20, and a watch worth £8 8/. Some alterations were made to his mother's house to fit it for the reception of his proposed wife. During June and July he had a cold, and contracted a tender throat. In consequence of this, he felt low and miserable. He spoke to plaintiff, saying - "Your first husband started with a sore throat, didn't he?" She said, "Yes." He said, "I think we had better postpone the marriage. She replied - "Oh, no, its going out at night that has given you a sore throat. When we are married you won't be running out after me." To that he (defendant) replied. "Well, I shall be glad when it's all over. " (A laugh.)

Apart from that letter, he had always regarded plaintiff as being a really nice young woman. At this stage the further hearing was adjourned until Monday.

From The Age of November 21, 1911 (see here)

The defendant gave evidence on Friday, and he was now cross-examined by Mr. Lewis. He admitted writing the following letter to plaintiff: -

Dear Miss Ewen, - I received your letter dated 9th August. You know very well I did not break off our marriage. You did yourself. I only wanted to put it off, as I was not well enough, and in no position to marry or go to the expense you wanted me to go to. After reading your letter, with its insulting remarks to my mother and family, I, too, thank God you took the course you did.

Mr. Lewis: Are the statements in that letter true? Witness: Yes, they are true. Plaintiff broke off the engagement herself. I regard her letter as being that of a vindictive woman. It was just a letter of abuse.

What is the meaning of this sentence in your letter- "I decline to go to the expense you want me to"? - Oh, she wanted things I could not give her. She also wanted a longer honeymoon than I could afford to take. I was not in a position to marry at the time. Why? - I had suffered losses because of Irish blight in the potato crop. Then, on account of my illness I was advised to go away on a holiday to New South Wales. Did you ever say that the marriage was broken off by mutual consent? - I never said that. I said that plaintiff broke it off.

Annie Park (11), of Garfield, said that, in regard to the trousseau for which plaintiff was charging, plaintiff had worn one of the hats, and on the present occasion was wearing one of the dresses.

Elizabeth Flett, of Bunyip, married woman, said that plaintiff had informed her that the engagement with Temby had been broken off, because he had deceived her people about the property. She also said that she was glad that she was not going to live at the place, as she did not think that she would get on with Temby's mother. Plaintiff, during the conversation between them, said : I wouldn't have him now not if he were hanging with diamonds." (A laugh.)

His Honor, in summing up, said that up to a certain point both parties were agreed. There was no dispute about the fact that plaintiff became engaged to defendant about Easter of last year. Both sides said there was not a ripple on the water of their happiness up to July last. Before that time there was no suggestion of a breach, of a postponement of the marriage. According to plaintiff, however, on Sunday, 30th July, he informed her he was going to break off their engagement. He promised he would go to plaintiff's residence on the following Tuesday to explain why, but he never went. Plaintiff then wrote a letter, about which there had been much discussion, and defendant wrote a reply. Defendant's version was that the marriage was merely postponed, and that on the Sunday all parties left on good terms. It was for the jury to judge which story was true.

Footnotes:

.jfif)